Unpacking the Nexus: Taliban's Control over Affiliated Terror Groups

Abstract

The contrasting statements made by US President Biden at a press conference in 2023 – that the Taliban would “help” and there is no Al Qaeda in Afghanistan – and the findings of the UN Sanctions Monitoring Team, which revealed the Taliban’s nexus with several terrorist organizations were met with a response from the Taliban expressing that the US recognized the on-ground reality. These developments have heightened the discussion about the Taliban’s established relationships and mutually advantageous associations with terrorist groups that have taken refuge under the Taliban government. In this context, this research scrutinizes the interrelationships among regional and global terrorist organizations, including the Haqqani Network, Al Qaeda, East Turkistan Islamic Movement, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, and IS-K, coexisting within Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. Additionally, it delves into the Taliban's strategic management of these groups, employing them as bargaining assets in negotiations with the United States and China to advance their national and global interests. This contributes significantly to our understanding of the potential threat posed by the Taliban's resurgence, emphasizing the risk of Afghanistan once again becoming a hotspot for terrorism. Consequently, endorsing the Taliban government could carry profound implications for global peace and security.

Keywords: Taliban, Haqqani Network, Al Qaeda, East Turkistan Islamic Movement, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, and Islamic State of Khorasan Province, China and the United States.

1. Introduction

The Taliban are a new reality in Kabul, Afghanistan. However, their interim government faces legitimacy challenges. Following the US withdrawal in 2021, the People’s Republic of China (in short, China) has taken the lead in engaging diplomatically with the Taliban. In light of evolving geopolitics, the US signed the Doha Accord, including undisclosed annexures defining its relationship with the Taliban. China, however, with its long covert relationship, proceeds cautiously in nurturing ties with the Taliban (Krishnan & Johny, 2022). The resulting security vacuum in Afghanistan has made the Taliban crucial for both nations, serving their security interests. Since the Taliban assumed power in August 2021, there have been no international-level terror attacks directly linked to Afghanistan-based groups.

Nevertheless, analysts warn of growing jihadi threats from Afghanistan as terrorist organizations gain momentum and greater freedom under Taliban rule (O’Donnell, 2023; Wood, 2021). Several experts, including Afghan sources, suggest the Taliban may possess the capacity to oversee and manage these impending threats effectively (Felbab-Brown, 2023; Groppi, 2021; Moonakal, 2023), while US President Joe Biden has downplayed Al Qaeda's presence, citing the Taliban's supposed moderation compared to the 1990s (Forbes Breaking News, 2023; Crowley, 2023). However, a recent report by the United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, released on June 1, 2023, which Afghan sources have independently verified, contradicts these claims (UNSC, 2023; Interviews, Pilani, June-September, 2023). It asserts the presence of numerous regional and international terror groups and their affiliates operating from Afghanistan, casting doubt on both China and the US's trust in the Taliban's capacity to control these terrorist outfits. The major regional and global terrorist organizations operating in Afghanistan include the Haqqani Network, Al Qaeda, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM)/Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)/Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP). The first four groups have affiliations with the Taliban, while the last one, ISKP, is considered a staunch adversary. Often, these terrorist organizations are in confrontations with major global powers, the US and China. However, the nature of their relationship with these major powers has evolved transitioning from being seen as freedom fighters during Soviet days to being branded as terrorists after the 9/11 attacks. This complex dynamic creates challenges for the Taliban in managing their relationships with these superpowers on one side while defending their historical camaraderie with terror groups on the other, upticking its terrorist credentials in the process.

Examining the origins of the Taliban and its sustained affiliations with the mentioned terrorist groups reveals a persistent global security threat to the interests of the US and China. The argument posits that it is premature for both countries to fully rely on the Taliban to combat terrorism stemming from Afghanistan. It emphasizes that, from its inception to its resurgence in 2021, the Taliban has incurred political, moral, and material obligations to various terrorist organizations. Consequently, the Taliban is deeply entrenched in the world of terrorism and possesses a limited capacity to control, manage, or influence these groups. While the US and China may support the Taliban against ISKP, they should engage other stakeholders to define terrorism and develop a comprehensive counterterrorism strategy instead of solely depending on the Taliban to address the challenges of terrorism.

Initially tracing the evolution of the Taliban and its interactions with terrorist groups in the Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) region, the text then briefly delves into the evolution of each terrorist outfit. It specifically focuses on the relationships the Taliban maintains with these groups and the reciprocation between them. The next section assesses the approaches of the United States and China in their engagement with the Taliban, driven by their narrow, short-term strategic goals. This engagement poses a risk to the region as it may revert to being a terrorist breeding ground, further destabilizing the already fragile security environment. The conclusion encapsulates the primary arguments and offers insights into how global powers can develop a better understanding of the Taliban, fostering a collaborative security framework for a more peaceful world.

2. The Taliban’s Evolution

During the height of the Soviet-Afghan war, the Soviets implemented a depopulation strategy, leading to approximately 6 million women and children fleeing abroad, primarily Pakistan. At the same time, men stayed back to fight (Colville, 1997). In Pakistan, ethnic Pashtuns coordinated fundraising efforts to acquire weapons and recruited volunteers to join their Afghan consanguine in the fight. They witnessed the emergence of over 80 factions, all asserting their dedication to a holy cause. Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) assumed control of the situation, benefiting from substantial resources provided by the US and Saudi Arabia to support the Afghan war effort seeking its strategic depth in Afghanistan (Crile & Lane, 2003). The ISI allocated funds, weaponry, and volunteer fighters to its preferred Pakistani groups, which in turn dispatched these resources across the Afghan border. Each of these Pakistani groups aimed to showcase their commitment to the Afghan cause by adopting increasingly radical Islamic ideologies, effectively normalizing extremism. By 1988, the Soviet war effort became unsustainable from all perspectives, especially financially, resulting in their withdrawal from Afghanistan. They left behind their communist-backed government, which subsequently fell to the Mujahideen. In 1992, Mujahideen forces overthrew the communist leadership, but they soon turned on each other in a bid to control different territories. This internal strife led to the emergence of numerous self-governing regions under the authority of various Mujahideen warlords.

Children who fled Afghanistan found refuge in Pakistani refugee camps, partly supported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (HWH, 2021). These young refugees attended Pakistani madrasas led by clerics affiliated with Islamist political parties in Pakistan. Over 2000 madrasas were established near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, where they were indoctrinated in the Wahhabi sect of Islam (HWH, 2021). In addition to religious teachings, many of these madrasas provided combat training, preparing students to fulfill the unwavering vision of establishing an Islamic state (Warren, 2009). These students became known as the Taliban, which means "students" in Arabic. A new generation of Afghan children, having sought asylum, began returning to Afghanistan with a determined goal to establish an Islamic State. In Kandahar, a Taliban cleric named Mullah Omar led a group of youngsters in taking control of districts previously held by Mujahideen forces. Local residents welcomed this transition, as many mujahideen groups had resorted to extortion, harassment, and persecution.

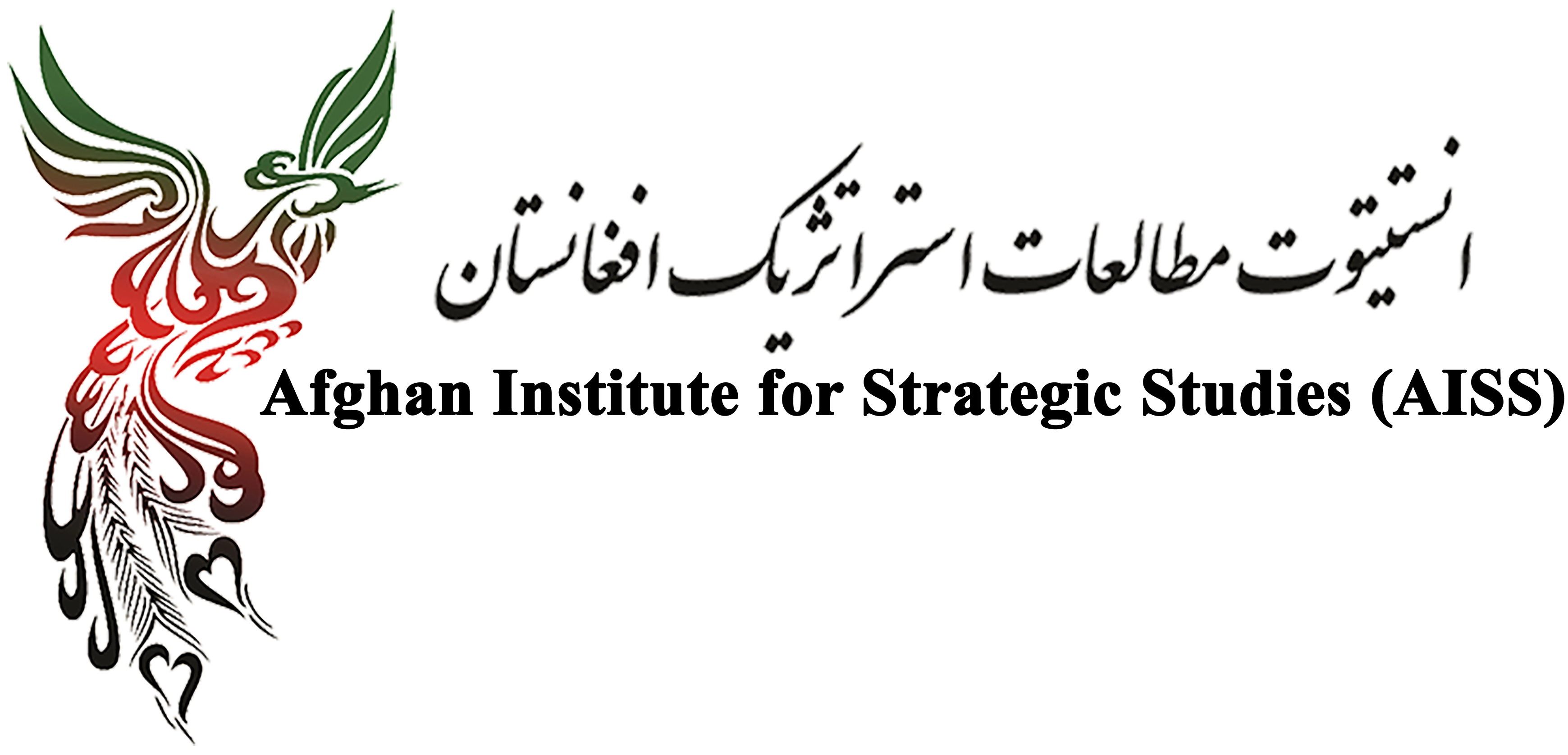

Figure 1: The Taliban's Traditional Stronghold

In contrast, the Taliban enforced strict Sharia law, carrying out punishments such as hanging rapists and severing thieves' limbs. The Taliban symbolized stability and security for most of the Afghan population (Rashid, 2000). These developments in Kandahar attracted the attention of Pakistan's security apparatus, leading the ISI to provide the Taliban with arms, funding, and training. By 1994, the Afghan Taliban had assumed control of vital border checkpoints between Afghanistan and Pakistan, facilitating the flow of goods into Afghanistan. Subsequently, the Taliban systematically captured cities across Afghanistan, including Herat, in 1995 and advanced toward the capital, Kabul, capturing it in late September 1996 (Rashid, 2001).

After the Taliban seized power, they imposed a stringent regime: women were barred from public life, and strict bans were enforced on music, films, and photography. Afghan traditions like kite flying were outlawed, and dress codes were dictated by Sharia law, mandating beards for men. Afghanistan transformed into a totalitarian state (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2001). During the late 1990s, the influence of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) over the Taliban began to wane, giving them space to operate more freely, and their ideology, often called Talibanism or Pashtun chauvinism, spread across the entire Af-Pak region (Cullather, 2002; Mather, 2003). During the years leading up to 2001, the Taliban undertook actions such as assassinating rival Mujahideen leaders, demolishing the sixth-century Bamiyan Buddha statues, and perpetrating targeted violence against religious minorities like Sikhs, Hindus, Ahmadi Muslims, Baha’is, Jews, and Hazaras (Mohammad & Udin, 2021). Women and girls experienced significant restrictions, with bans on education and employment, limited healthcare access, compulsory burqa-wearing, and the requirement to travel with male relatives in public (Mohammad & Udin, 2021). Moreover, Mullah Omar declared the establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, strictly governed by Sharia laws. However, the situation took a turn with the 9/11 attacks in the US. The Mullah Omar government's refusal to cooperate with the US in apprehending those responsible for the terrorist attacks prompted the initiation of the Global War on Terror (GWoT) by the US. This eventually led to the ousting of Mullah Omar, and the conflict endured for two decades until 2021. In this timeframe, Islamist militant organizations such as Al Qaeda and Haqqani supplied the Taliban with weapons, safe havens, and human resources. Simultaneously, countries like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan covertly provided funds to support the Taliban's efforts against Western forces (Kronstadt, 2009). With the departure of NATO forces in August 2021, the Taliban rapidly regained control, overthrowing the Ghani government and reasserting their dominance in Kabul.

Throughout their history, from their inception to the recapture of Kabul, the Taliban received support from various Islamist militant groups, and due to Pashtunization policies, they have maintained their stronghold on Afghanistan’s southern and eastern provinces, as shown in figure 1. Jill notes that their approval rating for governing stands at 30 to 45 percent, primarily coming from Pashtun-dominated provinces (Interview, Pilani, September 2023). Stephan Jensen adds that this approval is rooted in the Taliban's contemporary approach. They have become more skilled, have learned the nuances of diplomacy, improved their organizational structure, broadened their outreach, and are gradually seeking alignment with the global mainstream to avoid upsetting hardliners (Interview, Pilani, August 2023). However, Afghan sources, in agreement with Jill, report that the Taliban currently comprises 12 to 20 splinter groups. Prominent among these groups are the Haqqani Network, Al Qaeda, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. They also faced a formidable adversary in the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (Interview, Pilani, September 2023). Hence, understanding the intricate and symbiotic relationships the Taliban maintain with these Islamist militant organizations is crucial to comprehending how they support and bolster each other during both favourable and challenging times.

3. Taliban’s Relationships with Terror Outfits

3.1 The Haqqani Network

The Haqqani Network, a Sunni Islamist militant group formed in the 1980s, takes its name from its founder, Jalaluddin Haqqani. Jalaluddin, born in Paktiya province, Afghanistan, named the group after the Darul Uloom Haqqania madrasa in northern Pakistan, which he attended, as did Mullah Omar, the founder of the Taliban (Gul, 2016). Jalaluddin Haqqani gained prominence during the anti-Soviet jihad and even met US President Ronald Reagan, who hailed him as a freedom fighter (Alam, 2018). He played a pivotal role in assisting the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) by channeling arms and finances to support the Afghan resistance against the Soviet occupation (Van Dyk, 2022). Haqqani also called on Muslims worldwide to join the struggle against the Soviet Union's occupation, attracting volunteers from various regions, including Chechnya, Pakistan, and the Arab world. Among those who responded was Osama Bin Laden. This marked the beginning of a decade-long collaboration between the Haqqani Network and Bin Laden, during which they established an extensive Islamist network with the support of CIA funds, training, and ammunition in Pakistan, which also brought them into contact with the ISI. Throughout its history, the Haqqani Network was divided into four distinct groups: Soviet-era Mujahideen, Loya Paktika (since 2001) operating as guerrillas in southeast Afghanistan, recruits from North Waziristan since 2010, and foreign fighters from Arab nations, Chechnya, and Uzbekistan, among others (HWH, 2021a).

Following the Soviet Union's withdrawal in 1988, Afghanistan's Communist government, led by Mohammad Najibullah, faced increasing threats. In 1992, amidst a devastating civil war, Najibullah resigned. During this tumultuous period, the Taliban gained strength in southern Afghanistan. They collaborated with Jalaluddin Haqqani's network in 1994 to restore stability and defeat rival warlords (LaPorte, 1997). By 1996, with Pakistan's support, the Taliban assumed power, and Jalaluddin pledged allegiance to Mullah Omar, serving in the Taliban government (1996-2001) as Paktiya's provincial governor and the Minister for Tribal and Border Affairs (Stenersen, 2010). Following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Osama Bin Laden and Al Qaeda members sought refuge in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan with Haqqani's assistance.

During the GWoT, secret meetings were held with stakeholders, offering the Haqqani Network a role in the Karzai government. However, Jalaluddin Haqqani declined, choosing to support the Taliban against NATO forces from 2001-2021 (HWH, 2021a). Haqqani and the Taliban conducted numerous attacks, including a suicide bombing at Kabul's Serena Hotel in January 2008. They attempted to assassinate President Karzai during the 16th-anniversary celebration of the Communist government's fall in Kabul on April 27, 2008. In 2008 and 2009, suicide bombings at the Indian Embassy in Kabul killed 75 and injured 224 (Van Dyk, 2022). Journalist David Rodd was kidnapped from Logar province on November 10, 2008, while attempting to meet Taliban commander Abu Tayyab (Van Dyk, 2022). The Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul was bombed in 2011, and Afghan security forces intercepted a Haqqani truck bomb with nearly 28 tons of explosives in 2013 (Nctc, n.d.). UN reports highlight the Haqqani Network's critical role as the primary liaison between the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

The Haqqani Network engaged in activities such as extortion and kidnapping of government officials and Western citizens and had connections with wealthy Arab countries like Saudi Arabia and private donors to finance its operations. It's widely believed that the Pakistani establishment supported and funded the Haqqani Network (Reporter, 2017). However, in response to American pressure in 2014, Pakistan initiated Operation Zarb-e-Azb to expel them from the FATA and clear North Waziristan (Nawaz, 2016). Subsequently, the Haqqani Network shifted its operational base to the southeastern provinces of Afghanistan. The Haqqani Network played a significant role in providing materials like Potassium Chloride for the Taliban's bomb-making unit in Afghanistan (HWH, 2021a). Its core members were known for their expertise in carrying out complex attacks and providing technical skills such as constructing improvised explosive devices and rockets (HWH, 2021a). After the death of Mullah Omar in 2015, Sirajuddin Haqqani rose in prominence, deepening divisions between the Haqqani Network and Kandahari Taliban leaders. Following the death of Mullah Mansour in a 2016 US drone strike, Sirajuddin assumed the position of the Taliban's deputy emir (Zenko, 2017). Hibatullah Akhundzada assumed leadership of the Taliban and intentionally divided operational control of the Taliban's military forces between his two deputies, Haqqani and Yaqub, to prevent potential breakaway factions from forming.

Figure 2: The Haqqani Networks Traditional Stronghold

At the time of Jalaluddin Haqqani's death in September 2018, Afghan sources indicated that the Haqqani Network held substantial sway in Paktiya, Paktika, and Khost, as depicted in Figure 2 (Brown & Bergen, 2006). They were estimated to have between 10000 to 15000 fighters. To reinforce their ranks, the Haqqani Network maintained connections with groups in Pakistan, including al-Qaidaized Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HUJI). HUJI drew cadres from Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Jaish-e-Muhammad, Jamiat-ul-Ansar, and Sipah-e-Sahaba, serving to strengthen both Al Qaeda and, subsequently, the Haqqani Network (Rana & Gunaratna, 2007). Sirajuddin Haqqani took charge of the Haqqani Network. He is considered to be more fearsome and extremist than his father. Anas Haqqani, Sirajuddin's brother, was arrested in Bahrain in 2014 on charges of fundraising for the Haqqani Network and the Taliban. He was later sentenced to death by an Afghan court. While the Taliban spokesperson denied these charges and portrayed Anas as a religious student with no links to militancy, US military affairs expert Bill Roggio identified Anas as a key propagandist, fundraiser, and ambassador for the Haqqanis, primarily in the Arab world (Roggio et al., 2016). Additionally, a Der Spiegel report confirmed that Anas’s death sentence verdict was delivered under pressure from Afghan government circles. However, due to China’s intervention with the Kabul government, Anas could be saved (Koelbl, 2022).

Anas was subsequently released in 2019 through a prisoner exchange. Following the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan in 2021, Anas engaged in discussions with former President Hamid Karzai. Sirajuddin Haqqani's uncle, Khalil Haqqani, reportedly oversees security in Kabul, making the Haqqani Network a significant combat-ready element within the Taliban's interim government. They are integrated into the Taliban but maintain some degree of autonomy. Experts such as US Admiral Mike Mullen assert that Pakistan's security establishment sees the Haqqani Network as a valuable ally, using them as a proxy to advance their interests in Afghanistan and describing them as a veritable arm of the ISI (Reporter, 2017).

Since the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, the Haqqani Network has been intricately integrated into the governance system of Kabul. There have been reports of disagreements between the Haqqani Network and other factions within the Taliban. Former ISI Chief Faiz Hameed has raised concerns about Haqqani's deep links with ISIS (Gohel, 2021). Efforts have been made to resolve conflicts between Mullah Baradar and Anas Haqqani over control of the new government, with Hameed visiting Kabul for this purpose (HWH, 2021a). The Kandahari Taliban also appear to have a trust deficit with the Haqqani Network, leading to internal disagreements. A UN monitoring report highlighted these divisions and suggested that the Taliban government could face challenges in the coming months. Additionally, after the Haqqani Network, Al Qaeda has maintained long-standing ties with the Taliban.

3.2 Al Qaeda

In Arabic, the term "Al Qaeda" translates to "The Foundations." It is an Islamist militant group that was established by Osama Bin Laden in 1988. Bin Laden's ideology was influenced by the teachings of Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian thinker who is credited with inspiring the contemporary global jihadi movement (Gunaratna & Oreg, 2015). Bin Laden sought to rekindle orthodox Islam, as advocated by the Prophet himself, through a global jihad. This ideology is rooted in Salafism, a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam that seeks to return to the core principles of the Quran. It draws inspiration from Qutbism, a reformist movement within Islam that believed the religion had become diluted and departed from the teachings of the Prophet.

The backdrop of the 1979 Soviet-Afghan war saw Soviet forces intervening in Afghanistan to support a Communist regime. In response, various Afghan groups, including Unionists and university students, launched a rebellion. They referred to themselves as the "Mujahideen," a term in Islam denoting those who fight for righteousness. Prominent Afghan groups involved in this rebellion included Hezbi Islami, led by Gulbuddin Hekmetyar, and Jamiati Islami, under the leadership of Burhanuddin Rabbani. The military wing of Jamiati Islami, known as the Northern Alliance, was commanded by guerrilla leader Ahmad Shah Masoud (HWH, 2021c). Foreign fighters, organized by influential Palestinian scholar Sheikh Abdullah Azzam, also joined the cause, coming from 43 different countries to support the jihad against the atheist regime (Klausen, 2021).

Osama Bin Laden, hailing from a prominent Saudi family, responded to Azzam's call and gained prominence due to his financial resources and extensive connections in the Arab world. During this period, another influential Islamic radical from Egypt's Islamic Jihad group, Ayman al-Zawahiri, arrived in Peshawar. Bin Laden formed a closer association with Al-Zawahiri, distancing himself from Abdullah Azzam (Klausen, 2021). It was in Peshawar that Bin Laden and his associates founded Al Qaeda, an international Islamic organization, in 1988. Following Azzam's death in November 1989, Bin Laden and Al-Zawahiri began envisioning a broader mission that extended beyond Afghanistan's borders (Gunaratna & Oreg, 2015). They encouraged Muslims to take up arms against the West and its allies on their own soil.

The 1990 Gulf War served as the pivotal event shaping Al Qaeda's modus operandi, triggered by Saudi Arabia's rejection of Bin Laden's offer to secure its territory and its subsequent invitation to US forces. Bin Laden and other fundamentalists found it unacceptable to have non-Muslim troops stationed in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina (Klausen, 2021; Porter, 2003). In 1992, Bin Laden faced expulsion from Saudi Arabia due to his criticism, leading him to move to Sudan to assist the newly established Islamist government there. It was from Sudan that Bin Laden orchestrated his first terrorist attack against the US, targeting a hotel in Yemen where US forces were stationed as part of preparations for entering Somalia. By 1996, he had returned to Afghanistan, where the Taliban had assumed control of Kabul, forming the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan under the leadership of Mullah Omar. Discovering common allies among the Taliban, Bin Laden continued his activities discreetly, establishing the 055 Brigade, an elite unit of Al Qaeda-trained fighters in Afghan camps (Porter, 2003). Under the Taliban's protection, Al Qaeda escalated its global jihad agenda and issued a Fatwa, declaring jihad against the US and its allies worldwide. This Fatwa stemmed from Bin Laden's belief in a global conspiracy between the Christian West and international Jewry aimed at undermining and destroying Islam (Porter, 2003).

In 1998, Bin Laden conveyed his message to the world through the London-based Arabic newspaper Al-Quds al-Arabi, issuing his first Fatwa as the self-proclaimed Emir of Muslims: "It is an individual duty for every Muslim to kill all Americans and their allies wherever possible to liberate Al-Aqsa mosque and remove their armies from all Islamic lands." His intense hostility was further evident in a personal letter found in the Abbottabad safe house: "The United States is the head of infidelity. If Allah severed it, the two wings would not flutter" (National Geographic, 2022). Shortly thereafter, Al Qaeda launched a series of infamous terrorist attacks, including bombings at US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, resulting in 224 casualties. In 2000, the USS Cole, a US warship, was attacked off the coast of Yemen, leading to the deaths of 17 servicemembers (FBI, 2011). It has been reported that the US made numerous unsuccessful attempts, over 30 times, to persuade the Taliban's de facto government to sever ties with Al Qaeda (Miko, 2005).

On September 9, 2001, Al Qaeda operatives assassinated Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, and just two days later, on September 11, 2001, Al Qaeda executed the most significant terrorist attack on the US, targeting the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, which resulted in the deaths of over 2000 people (FBI, 2011). In his post-9/11 statement, Bin Laden remarked, "If only our messages to you had been conveyed through words, we would not have resorted to using planes (National Geographic, 2022)." In response, the US demanded that the Taliban hand over Al Qaeda members, a demand that was refused, leading to a forceful retaliation and the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 with support from the Northern Alliance.

The US-led invasion led to significant Islamist organizations leaving Afghanistan, and a democratic government, with Hamid Karzai at its helm, was established. In pursuit of the 9/11 perpetrators, they successfully captured Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the attacks (Liptak, 2007). Nonetheless, Al Qaeda remained undeterred and carried out the Madrid train bombings in 2004, resulting in the loss of 193 lives. In 2005, the 7/7 London bombings claimed over 60 lives (Zaidi, 2010). Al Qaeda persisted with the backing of the Muslim world. With each attack, the search for Osama Bin Laden intensified, culminating in the US Navy Seal Six team conducting Operation Neptune Spear on May 2, 2011, which targeted a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, ultimately resulting in Bin Laden's death (Klausen, 2021). However, while Bin Laden's demise weakened Al Qaeda's operational capabilities, it did not dismantle the organization. Ayman al-Zawahiri took on leadership, despite lacking the charismatic appeal of Bin Laden. Al-Zawahiri methodically expanded and strengthened the group by decentralizing power and creating independent cell structures across Africa, Europe, and Southeast Asia. This ensured sustainability even though regional key leaders were repeatedly taken out. From 2011 to 2021, Al Qaeda's terror threat remained relatively low and closely monitored. They continued to support the Taliban in their conflict against the West in Afghanistan but did not execute large-scale terror attacks. Despite this, NATO forces were unable to apprehend Al-Zawahiri.

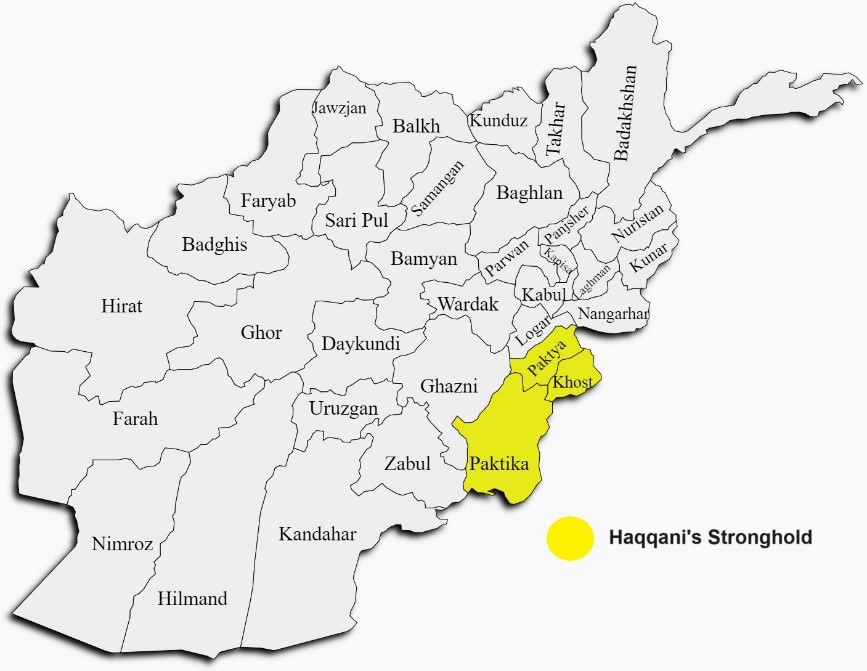

The Taliban's return to Kabul in August 2021 rejuvenated Al Qaeda, which viewed it as a triumph, given their two-decade support for the Taliban against NATO forces. Under Akhundzada's leadership, Al Qaeda members assumed advisory roles in security and administration, receiving regular payments. An Al Qaeda member oversaw the Ministry of Defence's training, following Al Qaeda manuals. Tajmir Jawed, a Taliban figure linked to Al Qaeda, served as Deputy Director of Intelligence. Qari Ehsanullah Baryal and Hafiz Muhammed Agha Hakeem governed provinces like Kapisa and Nuristan (Interviews, Pilani, June-September, 2023). Al Qaeda maintained a low profile, utilizing Afghanistan as an ideological and logistical hub for recruiting fighters and discreetly rebuilding external operations. The Taliban established "Department 12" within the General Directorate of Intelligence to supervise foreign fighters, including Al Qaeda members (UNSC, 2023). Since 2021, mapped in Figure 3, nearly 30 to 60 senior Al Qaeda leaders have been present in various locations, such as Kabul, Kandahar, Helmand, and Kunar. Al Qaeda fighters operated in different regions, including Helmand, Zabul, Kandahar (south); Ghazni, Kabul, Parwan (center); Kunar, Nangarhar, Nuristan (east). Training camps were established in Badghis, Helmand, Nangarhar, Nuristan, and Zabul, with specialized suicide bomber training camps in Kunar and Nuristan. Safe houses were identified in Farah, Helmand, Herat, Kabul, and also a media center in Herat (UNSC, 2023).

Figure 3: Mapping Al Qaeda's Senior Leaders' Bases in Green; Safe Houses in Blue; Fighters Stationed and Training Camps in Red and Suicide Bombers’ Training Camps in Grey

Al Qaeda was caught off guard when its leader, Al-Zawahiri, was killed in a US drone strike. This occurred just one year after NATO forces withdrew from the country, prompting questions about the Taliban-Al Qaeda relationship. Several possibilities are being considered: Did the Taliban disclose Al-Zawahiri's safe house location to NATO, betraying their camaraderie as per the Doha Accord's counterterrorism commitments? Alternatively, did the Haqqani Network sacrifice Al-Zawahiri for its own arrangements with NATO forces? Or did the Taliban adopt a double standard by concealing Al-Zawahiri in Kabul? President Biden's recent remarks that the Taliban would "help" hints at the first possibility. The truth about Al-Zawahiri's assassination may lie in the confidentiality of the Doha Agreement.

3.3 East Turkestan Islamic Movement

The Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP), referred to by China as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), is an extremist Uyghur organization that emerged in 1997 in Pakistan under the leadership of Abu Muhammad Al-Turkestani (Hasan Mahsum) and Abudukadir Yapuquan. It later relocated to Afghanistan in 1998 (Gunaratna & Oreg, 2015). ETIM's overarching goal is to liberate Xinjiang from Chinese control and establish an Islamic State, ultimately aiming for a Caliphate. While its roots trace back to Uyghur fighters who resisted Chinese authorities in the 1930s and 1940s, the formal organization was established in the 1990s (Castets, 2003). Despite facing defeat at that time and the imprisonment of Uyghur leaders, the movement persisted. Abdul Hakeem, a religious teacher released from prison in 1979, revived the movement. After Hakeem's passing, Dia Uddin Bin Yousef assumed leadership (HWH, 2022). In the 1990s, the group initiated its first armed uprising in Barren town, Xinjiang, which was met with a severe crackdown by Chinese authorities, resulting in the imprisonment of Uyghur leaders.

In the late 1980s, Uyghur unrest was escalating in China, while in neighbouring regions, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was collapsing. During the Soviet conflict, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) supported the Mujahideen resistance, with the CIA's assistance, providing training, weaponry, military advisors, funding, and human resources. Uyghurs were among the thousands of Mujahideen militants trained in camps located in Xinjiang (Engdahl, 2016). China also supplied them with military equipments, including machine guns and surface-to-air missiles valued at up to US$400 million (Panda, 2021). As the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989 and the Taliban gained prominence amid the Afghan civil war in 1996, Hasan Mahsum assumed leadership of ETIM in 1997. He travelled to various countries, including Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, in pursuit of support. However, official backing from Islamic nations was limited due to their desire not to provoke China. Consequently, Hasan Mahsum turned to non-state actors active in the Af-Pak region for support.

In 1997, he initiated the formation of the ETIM in Pakistan and unveiled a new campaign in Xinjiang intending to address past Chinese injustices, adopting a more violent approach to seeking independence. Subsequently, Hasan relocated the group's base to Afghanistan in 1998, where the Taliban held sway. During their time alongside the Taliban in Afghanistan, ETIM leaders maintained close ties with Al Qaeda's leader, Bin Laden (Rana & Gunaratna, 2007; Zaidi, 2010). Prominent ETIM members recount their encounters with Bin Laden. For example, Rozi, a prominent ETIM member, recalls that four members met Bin Laden and candidly discussed the organization they were forming, outlining their goals (CCTV, 2020). They made two key requests: a specialized training base for their members and economic assistance. Another ETIM member, Memet, admitted to spending three months in training camps, where they learned weapon use, bomb-making, and ideological principles. ETIM's military organizer, Qasim, described the intense training's rigour, which was so demanding that it could be fatal for those less resilient (CCTV, 2020).

While in Afghanistan, they established training camps to prepare volunteers for orchestrating attacks in China. ETIM operated under the protection of the Taliban until the occurrence of the 9/11 attacks. China actively supported the US GWoT, successfully persuading the US to designate ETIM as a terrorist organization. In 2001, the US invaded Afghanistan and conducted extensive airstrikes, destroying numerous ETIM training camps. In 2003, a US drone strike killed Hasan. After a brief period of inactivity, under new leadership led by Abdul Haq al-Turkestani, the group resurfaced in 2008, posing threats to the Beijing 2008 Olympic games (ETIM, n.d.; HWH, 2022). Although ETIM members held high positions within Al Qaeda and maintained close connections with Bin Laden, they officially pledged allegiance only in 2016. The group's acts of terrorism primarily targeted China. A review of these attacks reveals an expansion in both scale and capability.

From 1990 to 1998, their focus was primarily on assassinating religious leaders and conducting low-intensity bombings across China. After re-emerging in 2008, they shifted their attention to targeting Chinese civilians in Pakistan and China, as well as paramilitary groups in Kashgar. They were also responsible for a bus bombing in Kunming and an attempted aeroplane hijacking in Urumqi. In 2010, a plot to attack an aeroplane was uncovered in Norway, while mainland China continued to face persistent threats (ETIM, n.d.). In 2014, they orchestrated a series of mass stabbings at Kunming railway station, resulting in over 100 casualties (Xu, 2014). From 2016 to 2021, they targeted the Chinese Embassy in Kyrgyzstan and attacked Chinese workers at the Dasu dam in Pakistan (Chen, 2016; Shakil, 2021). Intelligence sources indicate that since its inception, the ETIM's sole and primary target has been Xinjiang. Al Qaeda and the Taliban played a role in helping ETIM recruit terrorists and religious extremists from Xinjiang, who were then dispatched to conflict zones such as Syria and Iraq, notably in 2016. These recruits proved highly effective and pivotal during the Battle of Aleppo before returning to China (Vagneur-Jones, 2017).

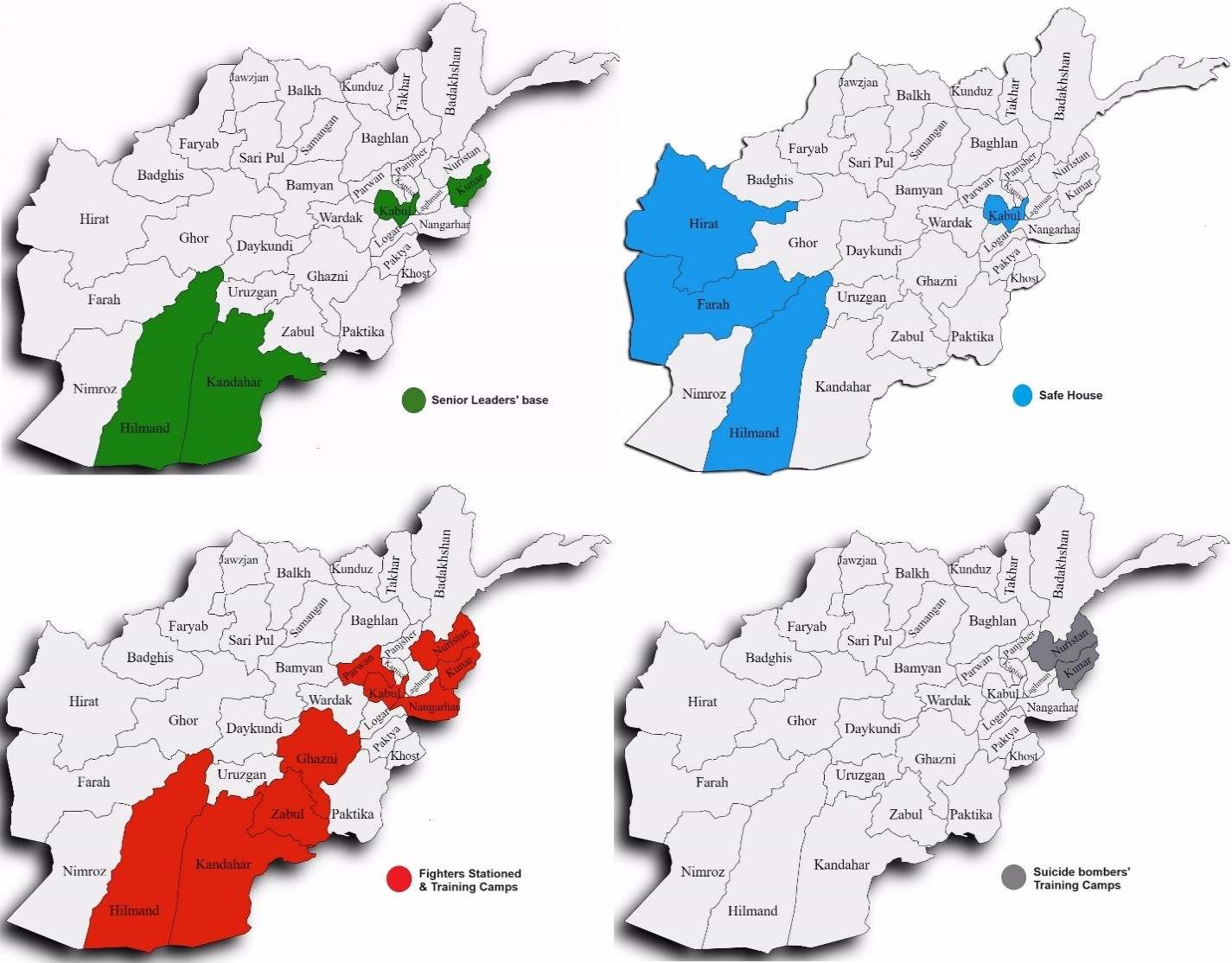

Figure 4: ETIM Fighters Stationed and Training Camps

ETIM maintained a close alliance with the Taliban across three key phases: during the Soviet war, the Taliban's first rule of Afghanistan (1996-2001), and the NATO invasion of Afghanistan (2001-2021). Despite the Taliban's assertions that they have eliminated ETIM training camps in Afghanistan under Chinese pressure, there are conflicting reports about the reliability of this claim. Hei Sing notes that the Taliban appears to uphold a double standard regarding ETIM. When questioned by the press about extraditing ETIM militants to China, Taliban spokesperson Suhail Shaheen did not provide a clear and affirmative response (Interview, Pilani, 2023). This ambiguous reply, as suggested by Shanthie Mariet D'Souza, might imply that the Taliban could potentially use Uyghur militants, just as they employ the TTP against Pakistan (Interview, Pilani, June, 2023). Currently, an estimated 800-1200 ETIM fighters operate in Afghanistan, establishing new bases in Baghlan province while maintaining a presence in Badakhshan, Takhar, Kunduz, Logar, and Sar-e-Pol provinces as depicted in Figure 4 (UNSC, 2023).

Abdul Haq and some ETIM members are said to have acquired Afghan passports and identity documents. Taking refuge in Afghanistan, they assist the Taliban in subduing anti-Taliban groups and covertly collaborate with entities like TTP, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the Islamic Jihad Group, and Jamaat Ansarullah (UNSC, 2023). Their objective is to infiltrate Central Asia, creating multiple channels to reignite terrorist activities in China. Recent reports reveal ETIM's involvement in training suicide bombers for ISKP and their collaborative propaganda efforts, significantly reshaping terrorist group dynamics in Afghanistan. This development has triggered concerns among the Taliban. However, Hei Sing holds the view that Uyghurs collaborating with ISKP in Afghanistan may face difficulties, considering the watchful eyes of the Taliban and Al Qaeda (Interview, Pilani, 2023). The relationship between the Taliban and ETIM appears to be deteriorating as they aim to avoid displeasing China and the Yuan. Jill suggests that the Taliban's priorities may not extend beyond Afghanistan, particularly concerning Muslims outside the country (Interview, Pilani, September 2023). Due to changing geopolitics, the US-Taliban agreement, and US-China rivalry, ETIM has been removed from the US-designated terrorist list. However, ETIM's activities persist, focusing on China.

3.4 Tehrik – e – Taliban Pakistan

Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, also known as the Pakistani Taliban, emerged in 2007 as an umbrella organization that loosely united approximately 12 distinct militant groups from the Af-Pak region. Led by Baitullah Mehsud, it shares similarities with the Afghan Taliban (Tehrik-e-Taliban Afghanistan or TTA) (Zaidi, 2010). This organization operates from bases on both sides of the Af-Pak border but holds significant influence in Pakistan's FATA. Its roots can be traced back to the broader context of the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, which prompted Pakistan's military offensive in the Af-Pak border regions, known to shelter various terrorist organizations. This military action triggered a full-scale internal conflict in the FATA region, as tribal communities perceived this act as Islamabad's attempt to assert control in the area (Abbas, 2004; Giustozzi, 2021).

Al Qaeda played a pivotal role in FATA and supported the formation of TTP, bringing together fighters from diverse backgrounds, including Arabs, Chechens, and Central Asian Muslims (Siddiqa, 2011). While the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban share a common name, ideology, and adherence to Pashtunwali cultural norms, they consider the Western world as a shared adversary. However, a significant distinction lies in their primary objectives: The Pakistani Taliban's main goal is to destabilize the Pakistani state and establish a new one governed by strict Sharia laws. In 2008, Mullah Omar urged TTP to cease its attacks on the Pakistani establishment, which had been providing support to TTA through clandestine channels (HWH, 2021c). In 2009, the TTP initially aligned itself with and supported the TTA in its resistance against the increased presence of US troops in Afghanistan (Giustozzi, 2021; Fair, 2018). However, this collaboration eventually broke down, leading to internal conflicts and divisions within various tribal factions following different sects in South Waziristan, FATA.

In 2010, the TTP underwent a profound transformation as its chief, Baitullah Mehsud, became the focal point of a US drone strike, triggering a power struggle within the organization. Amidst the internal turmoil, Hakimullah Mehsud emerged as his successor, injecting a dose of audacity by issuing terror threats on US cities. The narrative unfolded further in 2013 when Hakimullah Mehsud met his demise in a drone strike, intensifying the already strained relations between TTP and TTA, as documented by Giustozzi (2021). The ensuing tension spilt over into conflict in Kunar province, Afghanistan, where TTP strategically utilized it as a base to orchestrate attacks targeting Pakistan's establishment (HWH, 2021c). Despite the tumult, a ray of hope emerged in 2014 when TTP entered negotiations with Pakistan. However, this optimism was short-lived as several break-off groups, including the defiant Ahrar Hind, declared separation, only to later reconcile. The rollercoaster of peace talks and conflict reached a crescendo with TTP orchestrating multiple suicide bombings and collaborated with the IMU in a brazen attack on Karachi airport in 2014.

In the same year, they executed a devastating attack on an Army Public School, resulting in the deaths of over 149 people, mostly school children (United States Department of State, 2017). This prompted the Pakistani military to launch Operation Zarb-e-Azb in Waziristan. Interestingly, when the Taliban took over Kabul in 2021, they executed Omar Khorasani, the individual behind the Army Public School attack, calling it un-Islamic (UNSC, 2023). This operation, Zarb-e-Azb, had a significant impact, pushing TTP on the backfoot. TTP fighters sought refuge under Hafiz Gulbahadur and Maulvi Sadiq Noor, who were ultimately under the protection of the Haqqani Network. This convergence point in Waziristan in 2014 saw Hafiz Saeed Orakzai announce the formation of the Islamic State of Khorasan Province in Pakistan, with fighters defecting from various terror groups that had sought refuge in Waziristan, including TTP and ETIM (Garret Johnson, 2016).

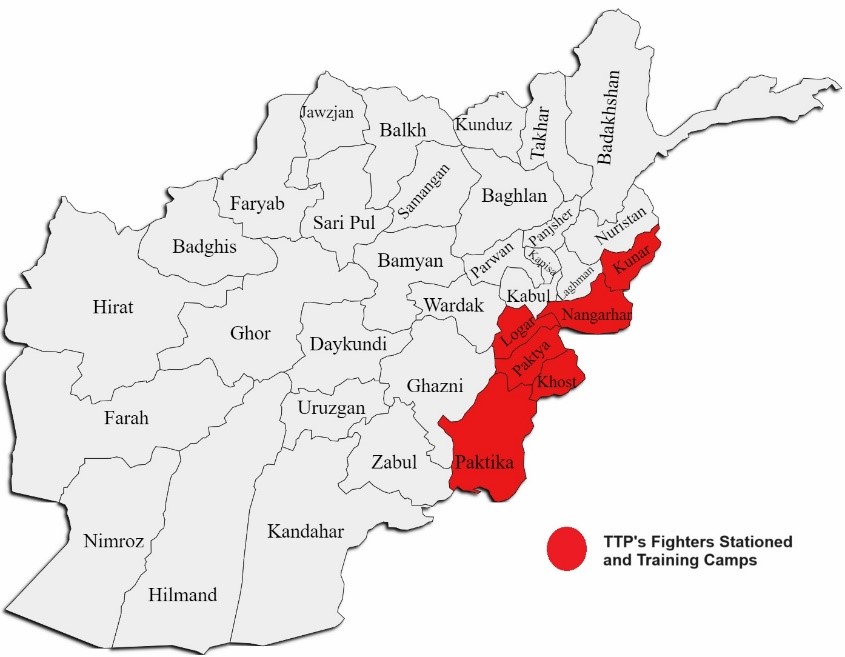

Figure 5: TTP Fighters Stationed and Training Camps

Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud currently leads TTP from Paktika, with Qari Amjad Ali as a deputy in Kunar province. Since August 2021, more than 2300 individuals have been released from prisons, significantly bolstering the TTP's human resources. TTP spokesperson Muhammad Khorasani, originally from Gilgit Baltistan, pledged their allegiance to Hibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban's supreme leader, and announced their immediate objective to gain control of the Af-Pak border region (UNSC, 2023). On November 9, 2021, TTP and Pakistan declared a one-month ceasefire, with Pakistan releasing over 100 TTP fighters as part of the agreement. Multiple ceasefires followed, but they concluded on November 28, 2022, when the TTP chief ordered its militants to commence nationwide operations. On January 30, 2023, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, a militant organization that merged with the TTP in 2020, carried out a devastating attack on a mosque in a Peshawar police compound, resulting in the deaths of 84 people. This was seen as retaliation for the killing of its leader, Omar Khalid Khurasani, who also served as the deputy of TTP. Afghan sources have suggested that Al Qaeda members are providing training and ideological guidance to TTP in suicide bomber training camps. TTP’s estimated strength in Afghanistan is around 4000 to 6000 fighters, with a significant presence in eastern provinces like Nangarhar, Logar, Kunar, Paktika, Paktiya, and Khost, as shown in Figure 5 (UNSC, 2023).

Over the past two years, TTP has executed more than 250 attacks targeting Pakistan's establishments. Nevertheless, the Taliban interim government has been consistently attempting to facilitate long-term peace talks between TTP and the Pakistani establishment. In these negotiations, the TTP's primary demands include the complete withdrawal of Pakistani troops from the Tribal areas, the safe return of TTP members to FATA, granting relative autonomy to the region, and the release of additional TTP prisoners (Devasher, 2022). On Pakistan's side, the demands entail the complete disbandment of TTP as an armed group and the renunciation of its fight. Given Pakistan's weakened position, it remains uncertain whether TTP will acquiesce to the demands of the Pakistani establishment. In a discussion, Devasher, an expert on Pashtun-related issues, asserts that neither TTP nor TTA recognize the Durand Line, and the rise of TTA within Afghanistan has intensified TTP's aspiration for the Islamic Emirate of Waziristan. Notably, the Taliban does not view TTP as a threat but as an integral part of the Afghan Emirate (Def-Talks, 2023).

3.5 Islamic State of Khorasan Province

The Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP or IS-K) emerged as an offshoot of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). The term "Khorasan" historically referred to a region encompassing parts of Turkmenistan, Eastern Iran, and Northern Afghanistan. In Islamist contexts, it can denote a larger area possibly extending into India. ISKP was established in 2014 as a breakaway faction by Hafeez Saeed Khan and Abdul Rauf Aliza, both former Taliban members who had become disenchanted with the group (Garret Johnson, 2016). Initially comprising around 60-70 fighters from the Levant, they aimed to create new factions in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region, mainly recruiting dissatisfied Taliban members (Jadoon et al., 2018). ISKP has been identified with members ranging from Pakistan to Turkey, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Notably, they have successfully attracted individuals from universities and the middle class in Afghanistan, a departure from the Taliban's traditional recruitment base (HWH, 2021c).

Soon after its inception, ISKP clashed with the Taliban and became a target for both the Taliban and NATO forces, as well as the Afghan government. The Taliban's objective centred on establishing an Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan with a more nationalistic focus (HWH, 2021c). In contrast, ISKP aspired to establish a Caliphate under the rule of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, pledging loyalty to him as the Caliph, a role holding religious and political authority over all Muslims. However, this notion was rejected by both the Taliban and Al Qaeda (HWH, 2021d). While they were willing to acknowledge an Emirate, they opposed the concept of a Caliphate due to its profound religious significance and the Caliph's supreme authority over the entire Muslim world, a power neither Al Qaeda nor the Taliban were willing to cede. These differences led to divisions among terror groups based on their interpretations of these concepts. Despite their fundamental ideological disparities, the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and ISKP all sought to recruit from the same pool of traditional rural Islamic populations to wage wars against their respective adversaries. Concurrently, there was a practice of poaching fighters from each other's ranks, further complicating the dynamics among these groups (Felbab-Brown, 2023).

ISKP experienced an early boost in 2015 when the IMU joined its ranks (Sharipzhan, 2015). Hostilities began in February, marked by the killing of Taliban commander Abdul Ghani by ISKP militants in Logar province, followed by clashes in Farrah province in May (Allam & Mekhennet, 2021). Subsequently, the Taliban leader in Nangarhar province and his small group were captured by insurgents. In June, the beheading of 10 Taliban members was filmed by the Islamic State and used for propaganda purposes (Azami, 2015). By November, ISKP's influence had expanded considerably, leading to severe infighting among different factions within the Taliban in the Af-Pak region. Part of this internal strife was also related to the news of the death of the Taliban's founder, Mullah Omar, which had been kept secret for two years. Mansoor Dadullah, the son of an Afghan commander who had died in the late 2000s, broke away due to disagreements over the choice of a new Taliban leader, thus pledging allegiance to ISKP. This split occurred in Zabul province and resulted in significant clashes between Dadullah's group and Taliban loyalists, ultimately leading to Dadullah's death (News Desk, 2015).

However, the Taliban soon regained lost ground against ISKP and launched offensives in their stronghold in East Afghanistan, specifically in Logar, Kunar, and Nangarhar. The Taliban managed to push ISKP back to just two villages in Nangarhar. Surprisingly, US drone strike support proved detrimental to ISKP, as did the Taliban's offensives. In August 2016, Hafeez Saeed Khan, the ISKP founder, was killed in a US drone strike. ISKP also suffered a defeat in the Farah region of southern Afghanistan at the hands of the Taliban, with the Taliban reportedly receiving Iranian military support in this conflict, according to ISKP. The estimated number of ISKP fighters decreased from around 2500 in 2014-2015 to approximately 1000 in 2017 (Allam & Mekhennet, 2021).

In June 2018, Russian officials held a meeting with the Taliban, which was widely criticized for legitimizing the Taliban to combat ISKP. Following this meeting, a high-intensity Taliban offensive occurred, with fighters from its stronghold in Helmand participating. They managed to dislodge several hundred ISKP fighters from Jowzjan in the disastrous Darzab conflict (Ramani, 2018). While ISKP received reinforcements from IMU militants, their combined efforts couldn't withstand the Taliban's offensive. Seeing defeat looming, the IMU commander struck a deal with the Afghan government, allowing them to be taken into custody while Afghan forces targeted the Taliban (HWH, 2021c). This did not weaken ISKP, and further fighting occurred between the two groups in Sar-e-Pol.

In 2019, ISIS weakened in Iraq and Syria, causing Af-Pak-origin militants to return to Afghanistan. This influx increased ISKP's strength, experience, and knowledge. ISKP shifted its focus to suicide bombings targeting Western interests in Afghanistan, using propaganda videos effectively to attract Afghan recruits by portraying themselves as the primary Islamic resistance against Western forces. Despite facing numerous defeats, this recruitment strategy allowed ISKP to maintain control, especially in Kunar province and other eastern regions of Afghanistan. Throughout 2020, ISKP planned multiple attacks on universities, schools, and mosques during Eid ul-Fitr. One of the most devastating attacks targeted a school in a Shia neighbourhood in 2022, resulting in the deaths of several hundred people, primarily young schoolgirls. The growing strength of ISKP, along with the Taliban's diplomatic efforts to negotiate with the US for peace in Afghanistan, created a division between the Taliban in the Doha political office and those actively fighting on the battlefield (HWH, 2021c). The latter believed that the Doha Taliban was compromising their conservative and extreme beliefs.

After the signing of the Doha Accord in February 2020, the Taliban launched an offensive against the Kabul government. This offensive led to the release and escape of numerous imprisoned ISKP fighters, bolstering their ranks. ISKP subsequently carried out two successful suicide bombings at Kabul airport during NATO's evacuation efforts, resulting in the deaths of 182 individuals, including 13 US soldiers (Allam & Mekhennet, 2021). Since the Taliban’s return to power, ISKP has intensified its attacks. In 2022, ISKP targeted the embassies of Pakistan and Russia, as well as the Longan Hotel in Kabul, frequented by Chinese nationals, in an attempt to disrupt the Taliban's international cooperation efforts (Washington Institute, 2023). They also made failed attempts to assassinate Sirajuddin Haqqani and Mullah Yaqub by entering their homes, demonstrating access to insider information. On March 9, 2023, they killed the governor of Balkh province, Mohammad Dawood Muzzamil, in a suicide bombing (Jazeera, 2023). A day earlier, they assassinated the head of the water supply department of Herat (Xinhua, 2023). On March 15, they failed in an attempt to assassinate the governor of Nangarhar province. In these attacks, ISKP reportedly employed the same 'hit-and-run' tactics that the Taliban had used against the former Afghan Republican government, involving roadside explosions and targeted killings.

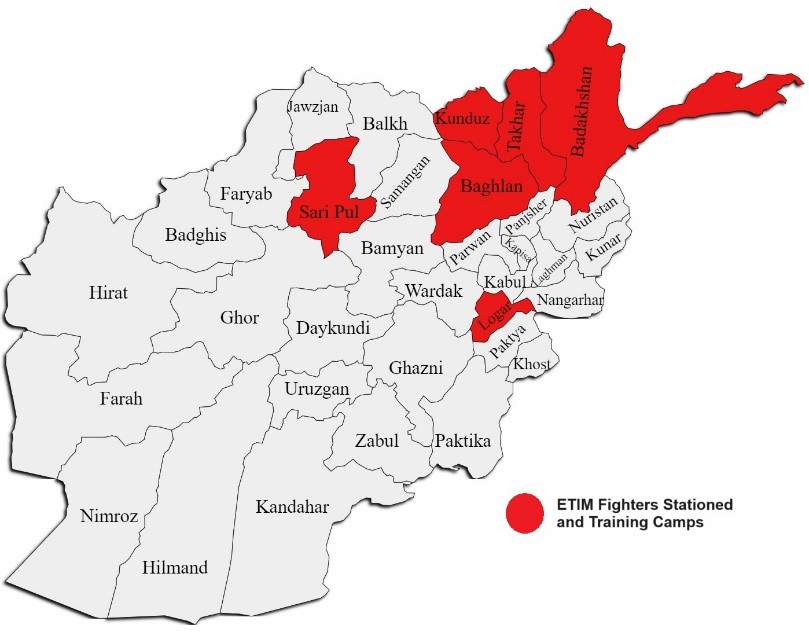

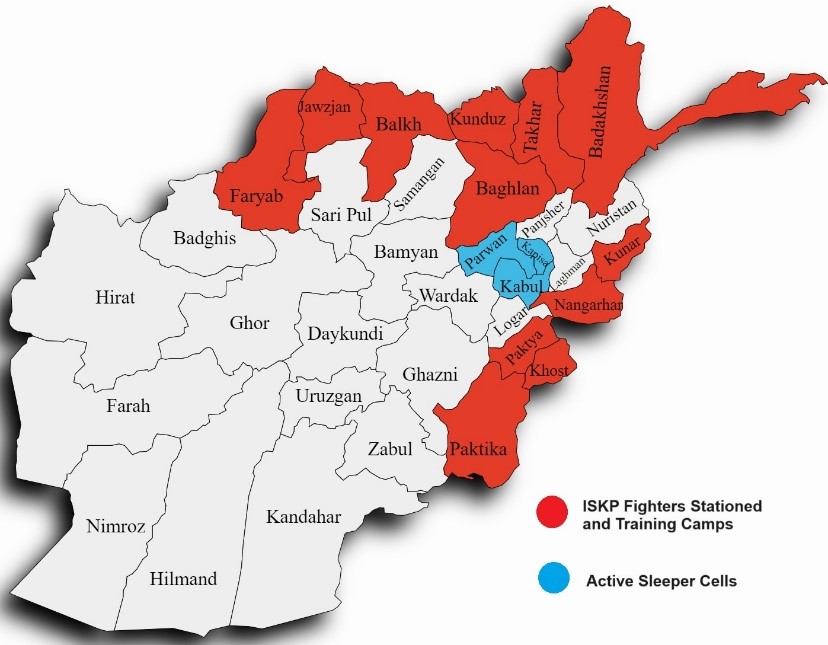

Figure 6: ISKP Fighters Stationed and Training Camps in Red; Sleeper Cells in Blue

Under the leadership of Sanaullah Ghafari, ISKP demonstrated operational prowess, reconnaissance, coordination, communication, planning, and execution. Ghafari's education and leadership abilities allowed him to recruit educated individuals, boost morale among his fighters, prevent defections, and enhance recruitment efforts. However, his death is a setback for ISKP (Gul, 2023). According to Afghan sources and Jill, ISKP's fighters number between 5000 to 8000, and they maintain training camps in Baghlan, Balkh, Jowzjan, Kunduz, and Faryab provinces in the north; Badakhshan and Takhar in the northeast; and Kunar, Nangarhar, Nuristan, Paktika, Paktiya, and Khost in the east. Additionally, they have an extensive network of sleeper cells in Kabul, Kapisa, and Parwan refer figure 6 (UNSC, 2023; Interview, Pilani, September, 2023).

Within ISKP's ranks, apart from foreign fighters, are former officials from the previous Afghan Republic, disaffected ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks, non-Salafists, and poached commanders from the TTP (Trofimov, 2021). Thanks to its effective media outreach, with Sultan Aziz Azam coordinating the Voice of Khorasan and the Al-Azaim Foundation publishing in 12 languages, ISKP has gained prominence. Jill observes that ISKP now stands as the predominant insurgent force in Afghanistan, presenting a credible challenge to the Taliban's authority (Interview, Pilani, September 2023), and James M. Dorsey characterizes it as a zero-sum game (Interview, Pilani, July 2023).

3.6 A Cumulative Analysis of the Taliban’s Symbiotic Relationships

A comprehensive analysis of the Taliban's engagement with these parent terrorist organizations, which wield substantial influence over extensive territories, boasts thousands of fighters specializing in various combat tactics, possessing technical expertise in bomb-making, and securing substantial funding for their operations alongside numerous affiliated groups downstream. This examination reveals several critical insights: Firstly, the Taliban maintains deep and interconnected relationships with these terrorist groups, accumulating significant political, moral, and material obligations over time for its survival and sustenance. Secondly, mapping these terrorist entities indicates that their presence is most prominent in southern and eastern Afghanistan, bordering Pakistan. Conversely, their influence is notably lower in northern, central-western, and western Afghanistan. Thirdly, the fact that the Taliban has established an interim government granting it control over all of Afghanistan, albeit somewhat tenuously, is only feasible due to the support provided by the human resources offered by these parent terrorist organizations.

Consequently, the Taliban's grip on Afghanistan depends on its ability to maintain this support. Fourthly, the Taliban's genuine apprehension regarding the Islamic State Khorasan Province is evident. As shown, ISKP maintains a substantial presence in northern Afghanistan, maintains active sleeper cells in the capital, Kabul, and its surroundings, and cultivates strong connections with local and smaller militant groups. Therefore, the Taliban's ability to combat splinter groups within its umbrella could lead to defections and bolster ISKP's ranks.

This raises the question of how the Taliban, whose survival in Afghanistan depends on these terrorist organizations, can take action against them to appease third parties like the US and China. This leads us to comprehend how the Taliban manages its interactions with the US and China.

4 US – Taliban – China Triangulate Relationship

The Doha Accord, also known as the US-Taliban deal, was signed on February 29, 2020. Despite intra-Afghan negotiations being a crucial part of the Doha Accord, they failed, prompting the Taliban to swiftly recapture Kabul on August 15, 2021. Following the Taliban's takeover, the US froze approximately $9.5 billion worth of Afghan assets abroad as a form of economic pressure (Mohsin, 2021). The US also imposed sanctions on the Taliban to push for changes in their policies regarding the rights of women and girls. However, due to the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, the US has provided about $1.1 billion in aid since August 2021 (US AID, 2022). However, the most significant aspect of the Doha Accord is the Counterterrorism Assurances, stemming from concerns about terrorism, especially after the events of 9/11 and the Taliban's lack of cooperation in addressing Al Qaeda in 2001. Under these assurances, the Taliban pledged that Afghan soil would not be used for planning terrorist attacks against any country. They also committed to cooperating with the US in countering terrorism emanating from the broader Af-Pak region.

Interestingly, the US was able to assassinate Al Qaeda Chief Ayman al-Zawahiri within a year of the Taliban's takeover. This feat had not been accomplished in the decade after the death of Osama bin Laden. This development has significantly disrupted Al Qaeda’s network. Ambassador Mohammad Zahir Aghbar, the Afghan envoy to Tajikistan, revealed that members of the Haqqani family were also killed in the US strike (Kumar & Ramachandran, 2022). Some experts speculate that the Taliban may have been providing cover for al-Zawahiri. In contrast, others believe that the Taliban may have disclosed al-Zawahiri's hideout in fulfilment of their counterterrorism assurances (Kumar & Ramachandran, 2022). This event has further strained trust within the Taliban interim government, particularly between the Taliban and the Haqqani Network, as the Haqqani Network plays a crucial role in the relationship between the Taliban and Al Qaeda. The Haqqani leadership feels betrayed and fears that the Taliban may comply with other US demands related to terrorism, which could put them at risk, according to Afghan sources.

During a recent press conference on June 30, 2023, President Biden stated that Al Qaeda's presence would not persist and that the Taliban would provide assistance. This suggests that the Taliban likely aided US intelligence in locating Ayman al-Zawahiri's hideout. By referring to the Taliban’s "help," President Biden implied their willingness to meet US counterterrorism demands to prevent a repeat of the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. Although Al Qaeda may still have a presence in Afghanistan, its operational capability has significantly deteriorated. The primary long-term terror threat faced by the West now comes from global jihadist organizations like Al Qaeda (which may regain strength over time) and ISKP. These groups have a broad reach, with the US and its allies as their prime targets.

According to reports from the UN Sanctions Monitoring and Afghan sources, these terrorist organizations remain active, maintaining training camps, stockpiling arms, and building operational capabilities (UNSC, 2023). Irrespective of the Afghan war's outcome, the past two decades have been a harrowing experience for the Taliban, constantly maneuvering to elude the threat from NATO forces along the Durand Line. Drawing valuable insights from their previous mistakes, the Taliban is now highly unlikely to lend support or provide shelter to terrorist organizations intending to target the US and its allies. Additionally, the Taliban faces significant threats from ISKP, known for its lethal and sophisticated attacks. To counter this threat, the Taliban requires US air support and intelligence cooperation. Therefore, at this moment, the Taliban needs the US more than the other way around.

With China, the Taliban have a long-standing relationship. In the winter of 2000, the former Chinese ambassador to Pakistan, Lu Shulin, met with Taliban leader Mullah Omar (Wion, 2021). During this meeting, Mullah Omar assured China that the Taliban would prevent any terrorism "spillover" into Xinjiang and affirmed that Uyghurs would not launch attacks in the region (Wion, 2021). However, he also mentioned that Uyghurs would remain within the Taliban's ranks. Since then, China has maintained a covert association with the Taliban (Panda, 2021). There have been reports of undisclosed meetings between members of the Doha Taliban and Chinese officials facilitated by Pakistani intelligence. On July 28, 2021, Beijing hosted a nine-member Taliban delegation led by Mullah Baradar. Similar delegations were received in 2019, while in 2015, China endeavoured to facilitate negotiations between the Taliban and the Ghani government. In these discreet interactions, Beijing astutely assessed the shifting dynamics of Af-Pak geopolitics, considering variables like the Taliban's capabilities, support machinery and territorial gains post the Doha Accord. Confronted with uncertainty about the future of Afghan politics, the Chinese government advocated for a balanced approach, exemplified by Xi's phone call with Ghani and Wang's meeting with the Taliban. However, Beijing clarified that it will do business with whoever holds power in Kabul.

While Kabul was in turmoil during the Taliban's takeover, China was one of the few countries that did not evacuate its embassy and personnel from the city. This demonstrated growing trust between China and the Taliban. It is also highly likely that the Taliban kept China informed about its plan of action to take over Kabul. Following the Taliban's capture of Kabul, China quickly established trade and commerce agreements with the de facto Taliban government (Amir, 2023). Various multilateral and minilateral dialogues, such as the 5th Multilateral Security Dialogue, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and others like the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan, China-Iran-Pakistan, and China-Russia-Iran-Pakistan dialogues, were conducted with China playing a crucial role in discussions about the Afghanistan situation. China actively pursued diplomatic ties with the Taliban regime, engaging in nearly 150 diplomatic interactions with the group after August 2021. On September 13, 2023, Afghanistan's acting Prime Minister, Mohammad Hasan Akhund, and Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi welcomed China's newly appointed ambassador, Zhao Sheng, at the presidential palace in Kabul (MFA_Afghanistan, 2023).

According to D’souza, China's engagement with the Taliban is primarily focused on securing strategic space (Interview, Pilani, June, 2023). Dorsey and Sarah Adam add that China is comfortable working with the Taliban because they are a non-transnational group with no interest in operations beyond their borders (Interview, Pilani, July, 2023). The Taliban aims to secure investments through projects like the Belt and Road Initiative and obtaining aid from China. They also seek entry into international organizations, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the United Nations. In return, China expects unwavering support from the Taliban in countering terrorism threats originating from the Af-Pak region, which include Uyghur militants, TTP, Al Qaeda, and ISKP. Uyghur militants pose a significant threat to China's Xinjiang province and could reignite the East Turkestan movement there. Adam says that China’s only motive with pre- and post-2021 Taliban was/is to gather information about the Uyghurs. The Taliban brokered this information with China in exchange for things they wanted, presumably mainly funding and/or weapons. Growing connections between Uyghur militants and other terrorist groups, along with their increasing operational capabilities to target Chinese interests abroad, have become a pressing concern. In 2021, the TTP, with elements of the ETIM, killed nine Chinese engineers working on the Dasu hydroelectric project, part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) (Shakil, 2021). In 2023, the TTP attacked Pakistani soldiers, securing the Xinjiang-Gwadar road, another CPEC component (Mashaal, 2023).

ISKP, a recent entrant, openly opposes China and supports Uyghur militants. In 2023, ISKP carried out a suicide bombing in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan while a top Chinese official was visiting Islamabad (MoFA, 2023). Yet, Stephan Jensen believes that the Taliban, with potential Chinese support, can effectively counter the much weaker ISKP (Interview, Pilani, August 2023). Mathieu Duchâtel, Deputy Director of the Asia and China Programme, has documented attacks on Chinese citizens and Chinese interests worldwide (Duchâtel, 2016). China's global presence makes it a prime target. While ETIM members remain within the Taliban's ranks, China's diplomatic efforts appear to have achieved partial success. The Taliban is amenable to locating Uyghur militants away from the Afghan-China border, but a complete disassociation remains elusive. In contrast, China's demand for security from terrorist threats converges with the Taliban's desire for diplomatic acceptance. This transactional relationship between China and the Taliban will likely continue to evolve in Afghanistan's complex landscape.

5. Conclusion

The Soviet-Afghan War and Cold War geopolitics spawned Mujahideen groups in the Af-Pak region. The Gulf War brought US troops to Saudi Arabia, angering some Mujahideen. The Taliban emerged from Pakistani madrasas and captured Kandahar and Kabul in 1996, forming close ties with radical Islamist groups. These groups’ members shared religious education, trained, and grew up in Pakistani refugee camps during the Soviet war. While the Taliban's goals were mainly rooted in Afghanistan, other Islamist organizations had global ambitions, leading to terrorist attacks in the 1990s, followed by the 9/11 attacks in 2001. The Taliban's refusal to cooperate with the US in the aftermath of 9/11 led to the US and its allies invading Afghanistan.

After two decades of conflict, the Taliban returned to power, and this signifies their success and is also a triumph for terrorist groups who supported them during the GWoT era. With the Taliban and its allies classified as terrorists, a crucial question emerges: Can the Taliban successfully control and influence the various terrorist organizations seeking refuge under its umbrella, steering them to advance their interests? Or will history repeat itself, with the world once again committing the error of placing trust in them?

One cannot ignore that the Taliban's recapture of Kabul is a cumulative effort of many terror outfits and ISI. These terror outfits helped reinstall the Taliban in power. The Taliban is now neck-deep in the world of terrorism (Kumar, 2021). Therefore, it is too early to think about legitimizing its interim government, given that its governance is criticized across all international platforms. Hei Sing argues that the US entered into confidential pacts with the Taliban to satisfy its near-term foreign policy and domestic interests, but it cannot turn a blind eye to the security black hole in Afghanistan (Interview, Pilani, 2023). Dorsey emphasizes the severe threats posed by ISKP and Al Qaeda and argues that China's only viable course of action is to arm and strengthen the Taliban, positioning them as the frontline of defence (Interview, Pilani, July 2023). The security vacuum in the Af-Pak region has, of course, made the Taliban a critical node in the counterterror strategies of both the US and China (Interview, Pilani).

However, it should not be forgotten that it is the Taliban that is providing blanket protection to other terror outfits. Therefore, it would be a grave mistake to trust the Taliban entirely on matters of (counter)terrorism as it would not be able to take action against those who favoured them during their earlier days of struggle. It would also be a mistake to consider that all terrorist units under Taliban cover are under Taliban control. Since there are clear indications and evidence of poaching of members among all terror outfits, it becomes challenging to identify which group committed an attack until one claims it or an extensive investigation is carried out to identify the culprit. Therefore, similar to the circumstances surrounding 9/11, even if the Taliban are not actively orchestrating or aiding terrorist attacks against any nation, they might be uninformed about such attacks being hatched within their territory by other terror outfits. A case in point is the TTP's conduct of over 250 low- and high-intensity attacks on the Pakistani establishment since August 2021, which the Taliban government vehemently disavows any connection to.

Jill acknowledges a significant trust deficit within the Taliban and concurs with the UN Sanctions Monitoring Report's assessment that the Taliban might not endure beyond 18 to 24 months (Interview, Pilani, September 2023). The Taliban's fragility requires constant monitoring of its activities as its fall may trigger intra-Afghan war. Given this complex situation, it is unwise to establish separate relationships with the Taliban. The US removing ETIM from its list of terrorist organizations and China using its veto to prevent the listing of other terrorist groups reflect unhealthy competition among nations, where non-state actors like terrorist organizations are part of geo-political power dynamics. Their specific interests in the region drive this selective approach to terrorism by the US and China.

In the case of Afghanistan, the US and China, in collaboration with other stakeholders, should closely monitor the Taliban's activities and the evolving situation in Afghanistan, as history could repeat itself. A stable Afghanistan is in everyone's interest, especially China (Verma, 2020). In particular, China should exercise increased caution, as it has become a new target for terrorist groups and has received numerous threats of potential attacks reminiscent of 9/11. The Taliban are a new reality; the world must unite against terrorism rather than fracture more.