The Death of Sandy Gall: The Voice Who Stood With a Wounded People

Sandy Gall, the British journalist, author, and documentarian, died on Sunday at the age of 97. He began his career at a local Scottish newspaper nearly seventy years ago, later working with Reuters and ITN. But in the memory of the Afghan people, he is not remembered for his titles or career milestones. He is remembered because he came close, because he entered the war, walked through valleys under fire, and told stories others refused to see. In the 1980s, while much of the world turned its back, Gall traveled to Panjshir and stood beside Ahmad Shah Massoud to document the resistance not from a safe distance, but from within.

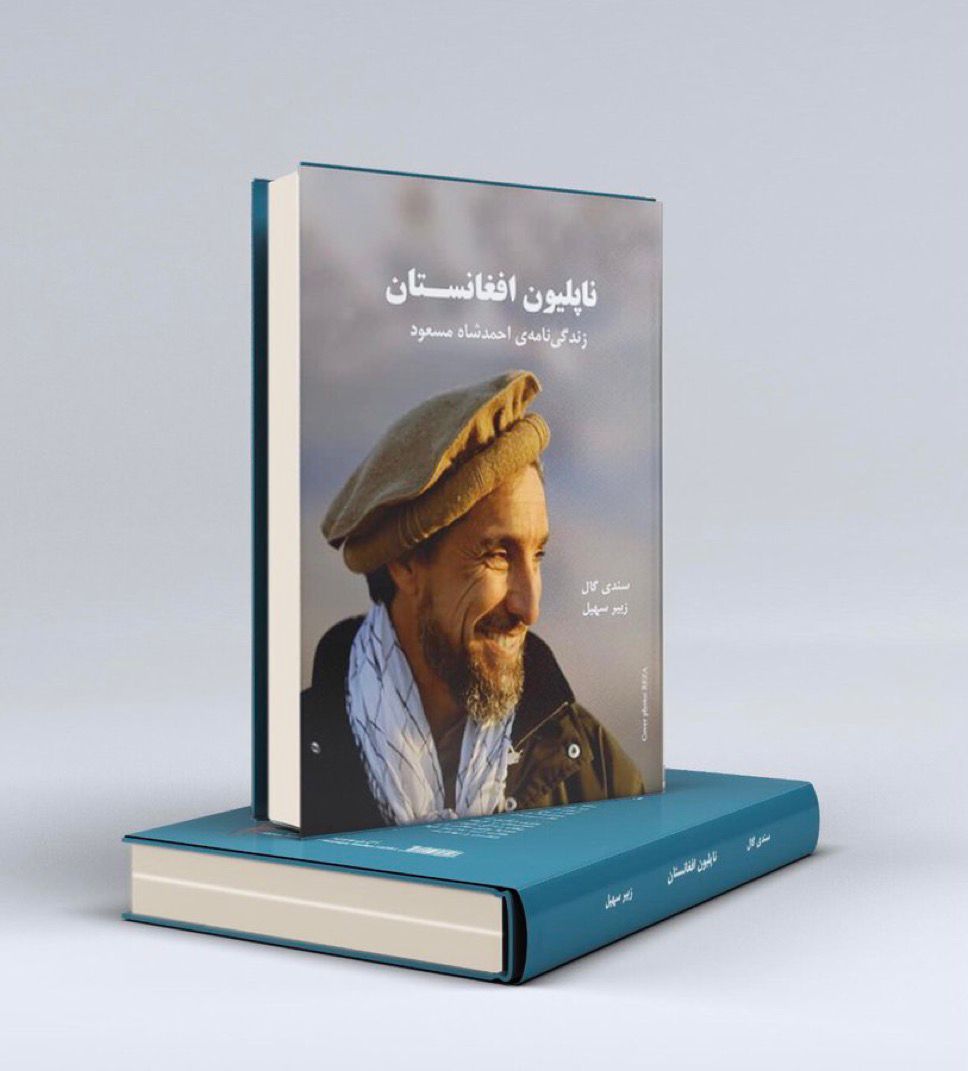

Over the course of his life, he wrote five books on Afghanistan and produced three documentaries on the Soviet invasion, two of which were nominated for a BAFTA. “Afghanistan: Napoleon of the East – The Life of Ahmad Shah Massoud” stands apart among them. It is not just a biography. It is a record of years of conversations, observations, and proximity to a man who embodied a generation’s refusal to surrender. The book was translated into Persian by Zubair Soheil and published in 2023 by the Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies.

His other books include “Afghanistan: Agony of a Nation”, “Behind Russian Lines: An Afghan Journal”, “Afghanistan: Travels with the Mujahideen”, and “War Against the Taliban: Why Everything Went Wrong in Afghanistan.” In 1983, shortly after broadcasting his first television documentary on the Afghan resistance, Gall also founded a charity, The Sandy Gall Afghanistan Appeal, which for four decades supported disabled Afghans, particularly war-wounded refugees in Pakistan. He was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1978 and later, the Order of St Michael and St George in 2011 in recognition of his long-standing work related to Afghanistan.

Sandy Gall was not a man of slogans. He was a witness. And he chose, again and again, to stand with a people caught in the crossfire of empires. His voice never sought to dominate—it sought to understand. And in that, he succeeded where many failed. He did not treat Afghanistan as a geopolitical subject or an abstract battlefield. He saw it as it was: full of faces, silences, wounds, and grace. Now that voice is gone. But his words remain, which became history instead of headlines.